The Hortus Conclusus of Barbara Baum

That first spring of enclosure Barbara was at work on landscapes. As we all went inside, her paintings stayed out, in clouded yellow fields.

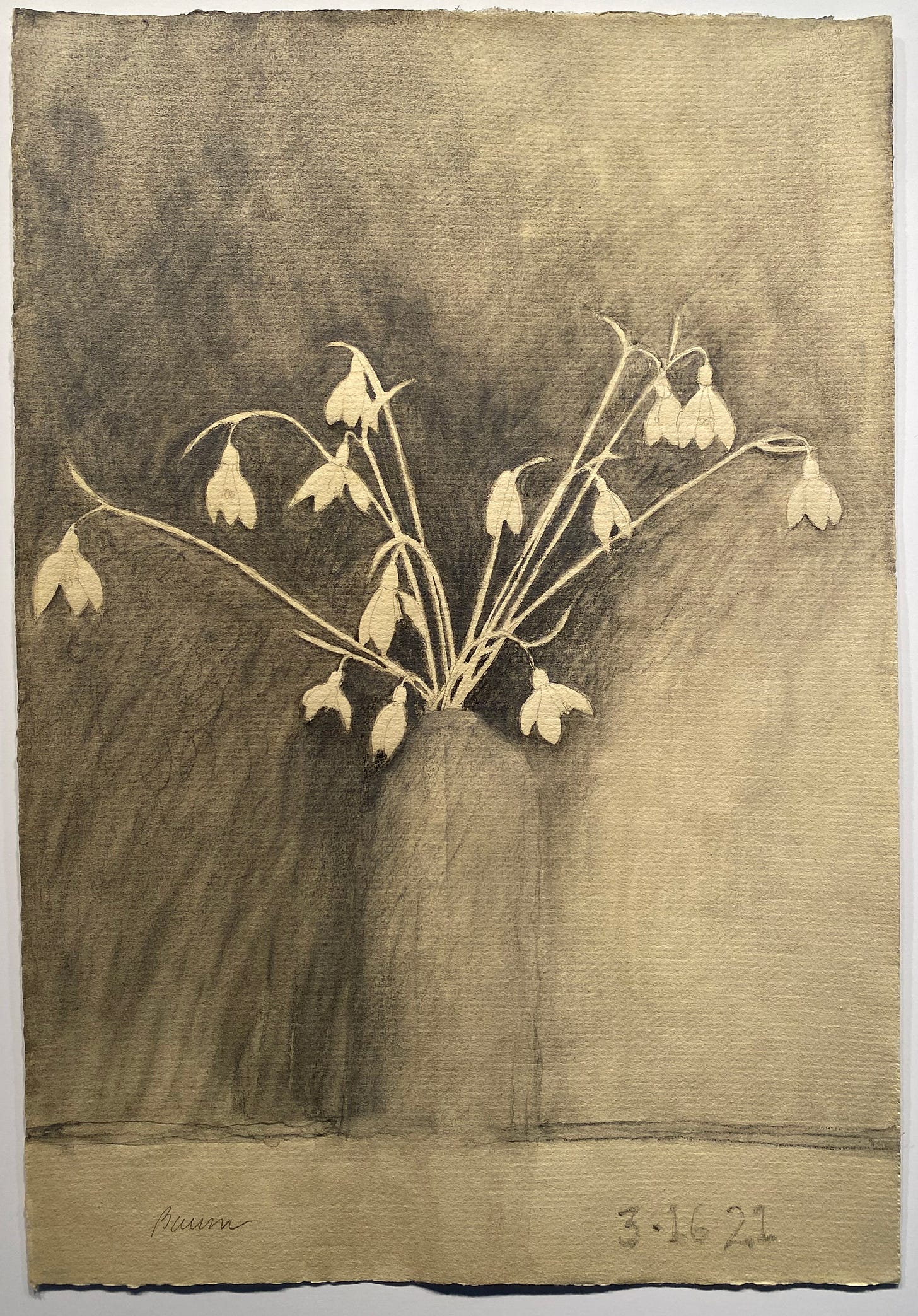

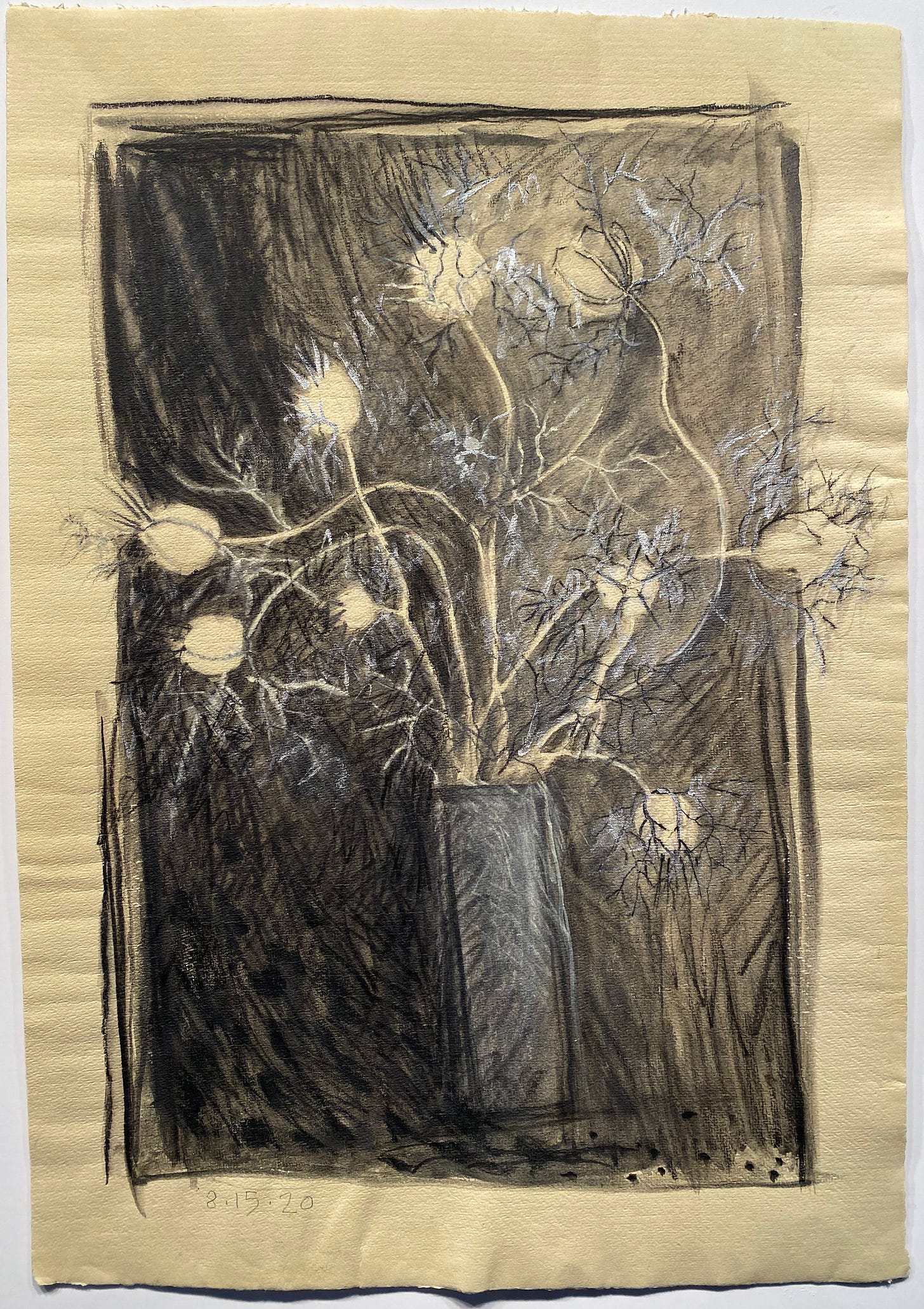

Once June came to Massachusetts, the flowers bloomed outside her studio, and in July she brought some in from her garden and set about to draw. Everything that she needed was already there: pencils and paper collected over the years, and the flowers she’d planted herself. She had chosen them to be hardy, to grow in the shade, a few for their strange forms.

Some have parts that can heal or hurt us. Daucus carota, our Queen Anne’s Lace that grows even where little else will, disrupts the estrous cycle.

Disease and death were so much about then, and beauty didn’t seem the point. When a bit of colour made its way in, Barbara would often take it right back out.

As if sitting by a window flooded with sun, the stuff of air comes into view, cosmos in a jar colliding with light and dust and oxygen.

Barbara had painted flowers on and off for many years. I have a memory of her coming in from the Red Line with a handful of blooms she’d used in teaching still life. She remembers gathering violets for her mother; finding a clump of daylilies in the woods; her father going out for doughnuts and bringing home a bunch of garden-stand wildflowers as well.

Clara Peeters also gives us flowers in this still life with pastry among other things. Tulips crowd in together with the humbler daffodil, buttercups mix with roses. The jug isn’t big enough for the poppy and peony strewn at its base. Flowers blooming all at once and out of time.

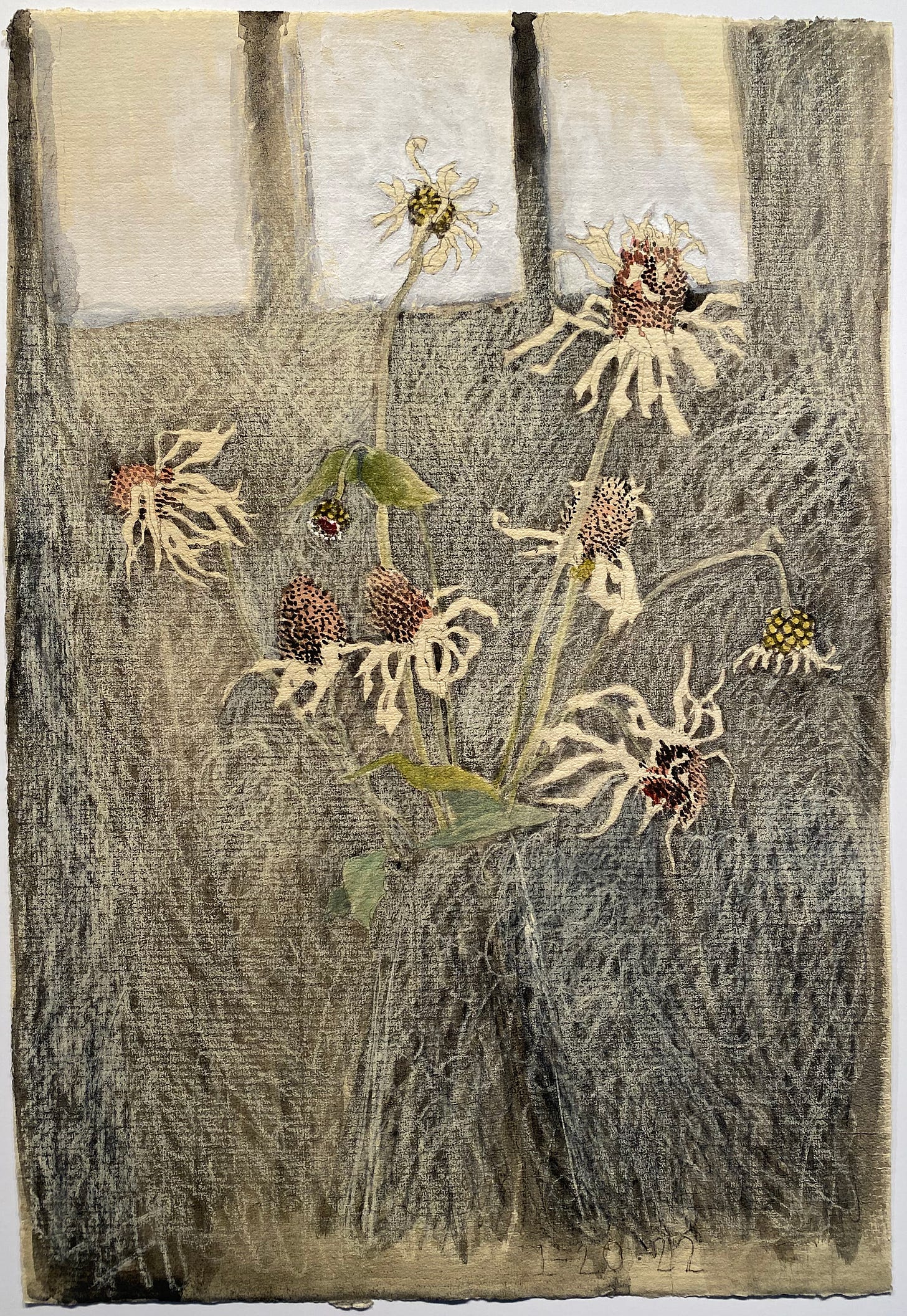

Putting her garden to bed in the fall, Barbara drew these cells in senescence, the flowers pressing outward as they go.

Clara, probably working from illustrations, wouldn’t have known dahlias, or zinnias like these. Named after the botanists Dahl and Zinn, these specimens of the Americas had not yet been introduced to Holland.

Making her own sort of introduction, Clara’s face bounces a few times off each metal surface in her painting. She’s there among the sweetmeats, by a window in the pitcher made of pewter. Yet almost nothing is known of her life: probably based in Antwerp; possibly trained by her father; perhaps worked for only fourteen years.

Barbara Baum came to Boston for art school in 1966. When no live model was scheduled, students would focus on still lifes: fruit, fish, a car muffler; but never the unserious flower. She trained with Richard Yarde and then with Philip Guston, staying on in the city, getting married, having children, painting at home in attic and basement rooms.

Over this two-year series Barbara has kept to few rules. Each of the flowers is given its own day, though most took more than that. Borders come and go; containers disappear; paint turns up. At some point, she begins to use a magnetite watercolour with a mind of its own. Particles of iron streak the page.

The flowers are nearly always hers. She went once to the shops and brought home anemones, unsure what to make of windflowers grown indoors. Marigolds not at their best she felt she knew better.

On certain days, she puts down her worries in the surrounding darkness. When Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s death is announced, she makes a note of it, as if these pages of flowers were a kind of daybook.

If this is a calendar, there are no reminders of what to do. Now is not the moment for sowing or reaping but for sitting at home and waiting. Can we hold on for as long as a zinnia?

Barbara didn’t think about showing the drawings to anyone. She’d often painted studies of flowers in between her grids and trees. At first, this seemed like that as well, an exercise mostly for herself alone.

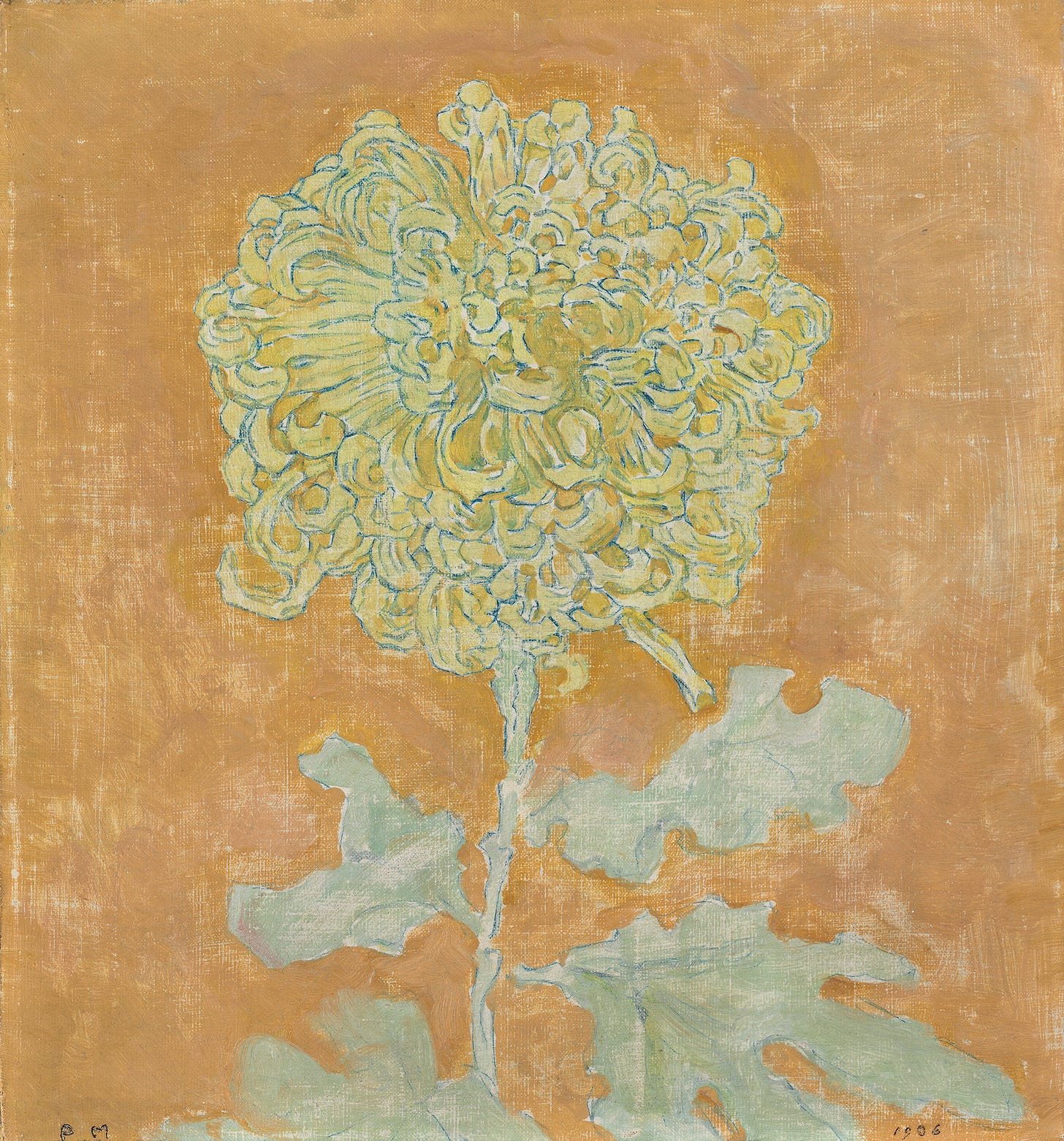

Piet Mondrian would have us think he painted flowers mainly for sale. When he needed the cash, no one buying his abstracts, he’d do a chrysanthemum or two. He only rarely gave these flowers a date, and later dated some to earlier than they were.

In 1919, Mondrian wrote:

If you follow nature you will not be able to vanquish the tragic to any real degree in your art…Let us recognize the fact once and for all: the natural appearance, natural form, natural color, natural rhythm, natural relations, most often express the tragic…We must free ourselves from our attachment to the external.1

He still brought flowers with him to New York. Charmion von Wiegand records seeing them on the walls of his spotlessly white kitchen in 1941.

Barbara keeps her flower pages in a box in her studio. As so often happens, days have gone missing — sold, thrown away, given to family and friends once she could see them again.

When Barbara knew him, Guston was painting still-life mounds of ripe cherries. In 1971, he made a series of drawings of Richard Nixon in action, a poppy’s stubble upon his jowls.

Guston recounted in 1977:

When the 1960s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to blue.2

Now that we know what will happen, we’ve almost forgotten our fright, the difficulty of seeing what was before us, and the relief we felt when the lilacs returned to blossom as they should. Barbara’s flowers, without sentiment or sweetening, bring that time back. Seed pods from a locked-down garden.

At work on a January morning, Barbara’s eye is on the zinnias in front of her, their prickly heads and splayed petals. Stepping away to have another look, she notices that it is beginning, again, to snow. One more flower and the box is closed.

Barbara Baum’s flowers are marvelous! You seem to know her so well.

Absolutely stunning. I loved reading (and looking) at this and would happily buy a whole book of these.