Somehow Aristotle also knew about elephants. He notes their unwieldy movements and large parts; trunks like hands and tusks as well as teeth. Long-living, though generation is slow and one-by-one.

Most of this elephant biology is accurate. He even corrects the observations of Ctesias about the consistency of their semen. One might be led to believe that Aristotle had seen these animals of Africa and Asia “copulating in lonely places” as well as dead and dissected.

For all of his understanding, Aristotle doesn’t come out well in elephant.

On the leftmost front section of this ivory box carved in Gothic Paris, lectures are in session. Aristotle sits with Alexander the Great, warning his adventurous pupil about the dangers of females. He points to some evidence in an open book, only to become his own example in the next scene.

Enticed by a young woman out to prove a point, he’s stooped low enough to let her ride him. Wisest of men, master of emperors, he’s still an akratic old fool. An ass wearing a bit and bridle.

Training an elephant is said to be easy. Yet as much as they make good soldiers or sideshows, this mammal’s curving incisors, good for defence, have always been our weakness.

Ancient sources mention houses and gates made from ivory and liken a beloved’s neck to an ivory tower. Furniture was inlaid with ivory, figurines cut from it. When elephant couldn’t be got, hippopotamus tusks or a more local animal’s bones might do.

Boxes, known in the literature as caskets, were sometimes given carved ivory sides; oblong and shoebox-sized, they are covered with lovers and fighters and zoos of animals.

Genesis opens on a box kept in Cologne. Adam, freshly created, starts naming things: “So Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the birds of the air, and to every beast of the field.”

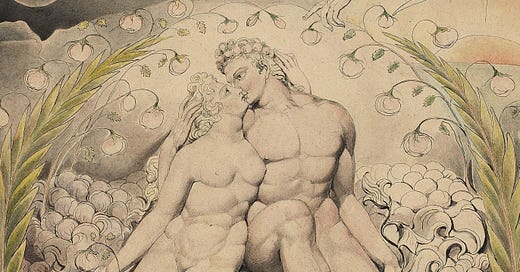

Doing God’s taxonomy, Adam faces his own singularity. He is alone with the animals of Eden. The elephant’s flesh and bones, its nose that wraps around trees, are nothing like his own. Eve is made to come and join Adam on the side of a box now in Cleveland.

This and a handful of other “rosette” caskets, made with tusks brought to Constantinople from Africa, present us with our sorry beginning. Eve and Adam Fall down the long exterior. Adam’s apple gets handed across pieces of ivory affixed to the box’s wooden core.

This pairing seems entirely right. Christian zoology tells us that elephants rest against trees and stand in for Adam and Eve:

There is an animal called the elephant whose copulating is free from wicked desire...If the elephant wishes to produce young, he goes off to the east near paradise where there is a tree called the mandrake. And he goes there with his mate, who first takes a part of the tree and gives it to her husband and cajoles him until he eats it.1

Leaving Eden, Adam and Eve are punished with lust, a sin the elephant seems to have escaped.

Made from luxurious bits of the modest elephant, the casket in Cleveland may have been intended as a wedding gift, a vessel to be filled with spices or perfume or coins. Adam and Eve are shown outside with nothing—not even clothes.

The first couple pause for a moment in their exile. Sitting apart, they look to be contemplating the damning events around the corner. Both hold their heads in grief. Between them would once have been the box’s lock. There’s no going back inside, and the real work of living needs to begin.

Adam and Eve never labour together in manuscripts; they have their separate jobs to do. He digs out thorns and thistles while she spins thread for their clothes. But ivories are a different matter.

On the back of the box in Cleveland, industrious man has moved from the fields into a forge. Adam is giving form to a lump of metal as Eve pumps on a set of bellows to feed the fire. The metal is hot and soft enough to be worked on the anvil.

It isn’t yet clear what they are making, but we’ve sped off far away from the slow grind of Genesis, in which a descendant of their disappointing son Cain is named as the first blacksmith.

Digging and harvesting and forging, Adam and Eve shape the earth as well as its metals. Versions of their story have Adam marching out of Paradise with a scythe over his shoulder. On ivory casket panels, more agricultural tools appear: hoes, and sickles, and even once a plough.

By the sweat of their brows, Adam and Eve have made the cursed ground fertile with grain. With their own sharp metal tools, the carvers of these ivories seem to be assembling the missing parts of our survival out of Eden—all that Adam and Eve must have known how to do.

Still, I wonder if there isn’t another layer to the odd scenes of primal smithery found only on these Byzantine boxes.

Genesis barely covers Adam and Eve’s postlapsarian sexual union: all we get is “Now Adam knew Eve his wife.” Few artists have attempted to interpret this brief encounter, though Cain is born outside the garden, followed by Abel.

Aristotle gives more detailed information on generation and genesis. Woman and man have different contributions to make: she is the material for the child; he provides its form. Aristotle compares the man’s role in conception to that of a blacksmith.

And just as we should not say that an axe or other instrument or organ was made by fire alone, so neither shall we say that foot or hand were made by heat alone...what makes them is the movement set up by the male.2

For Aristotle, reproduction is similar to the forging of an axe or a sword. Like Adam hammering away in Cleveland, the male with his active sperm is the real craftsman here:

Heat and cold may make the iron soft and hard, but what makes a sword is the movement of the tools employed.

Perhaps these glimpses of Adam and Eve at the forge were a reminder to the boxes’ newlywed recipients of the necessity of continuation for progress and prosperity. From ancient Greek epic to the gynaecomorphic furnaces across Central Africa, the forge has been seen as a place of sweaty procreation and parturition, where metals can marry, children get minted, and all of Nature’s creatures are pounded into shape.

Great read! Thanks for your insights and erudition.