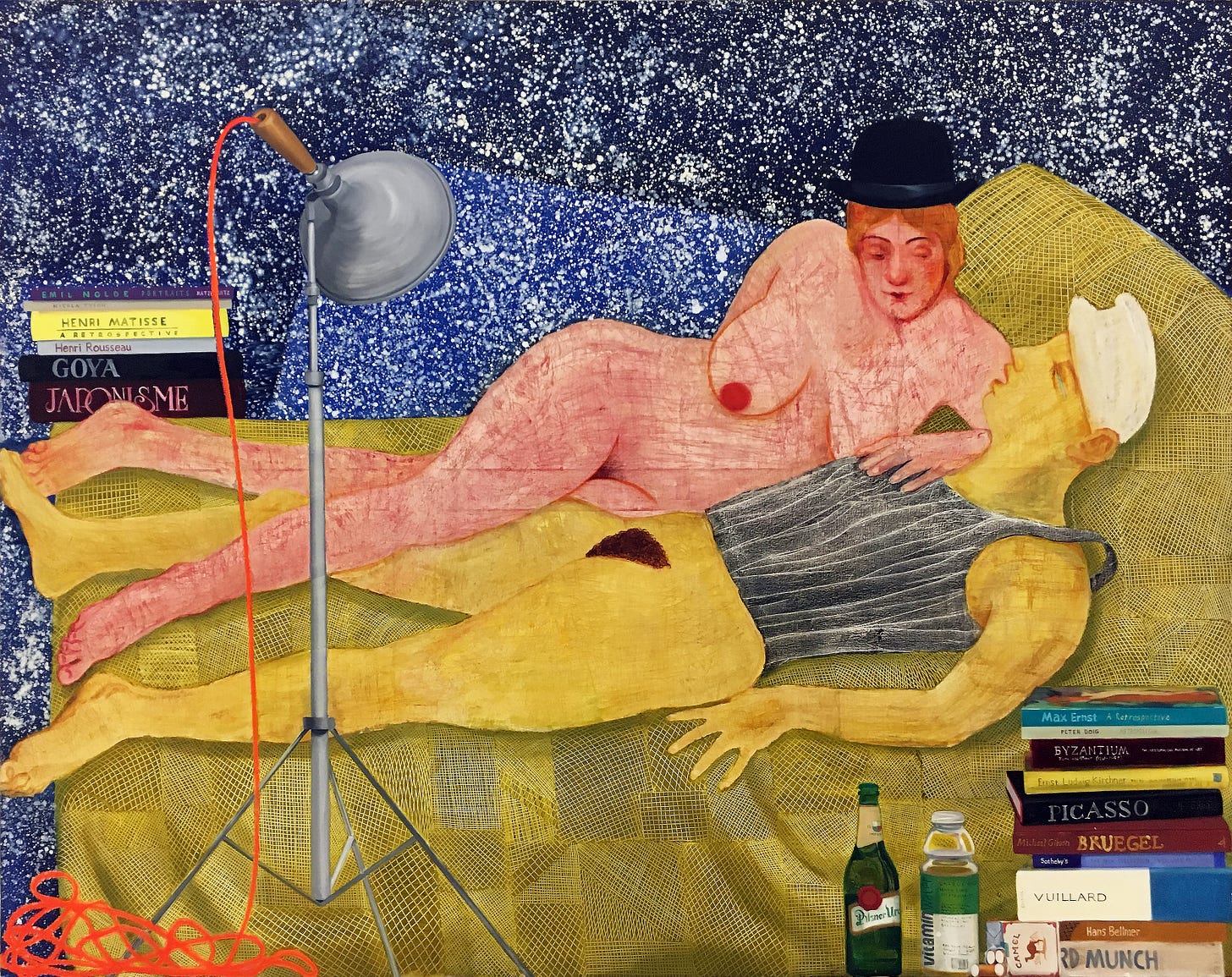

It isn’t obvious what has been going on in Nicole Eisenman’s Night Studio (2009). A pair of figures lies spotlighted on a mattress; one is propped up on their side, gazing down at the other, who looks perhaps to have dozed off. Does this scene of repose follow a leg over in the studio at night? Or is it instead just a couple of models weary after hours of being still?

Site of wondrous creation, the artist’s studio can also be a dull place. But refreshments are at hand, and, together with these items resting on the bottom edge of the canvas, is a stack of books.

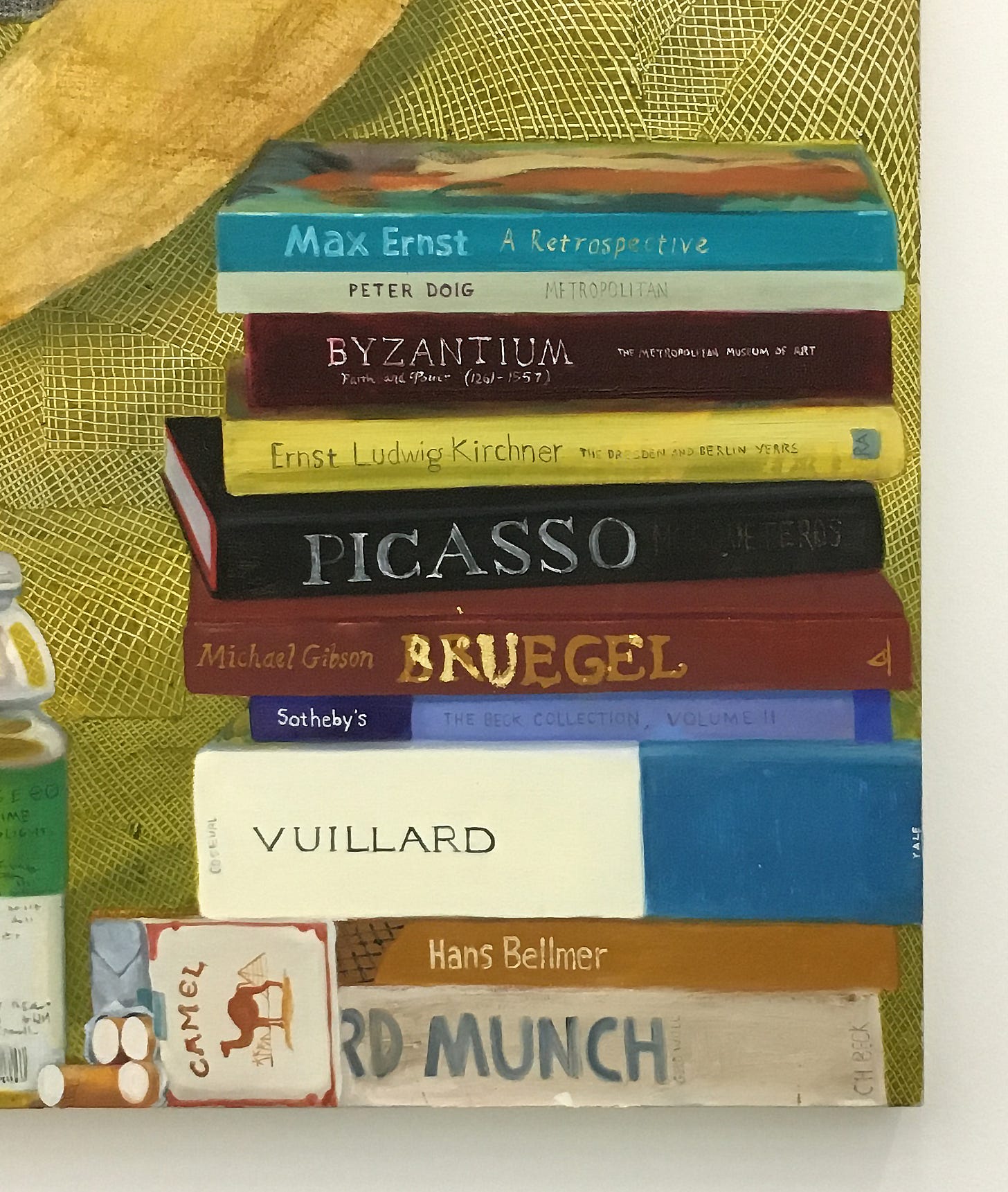

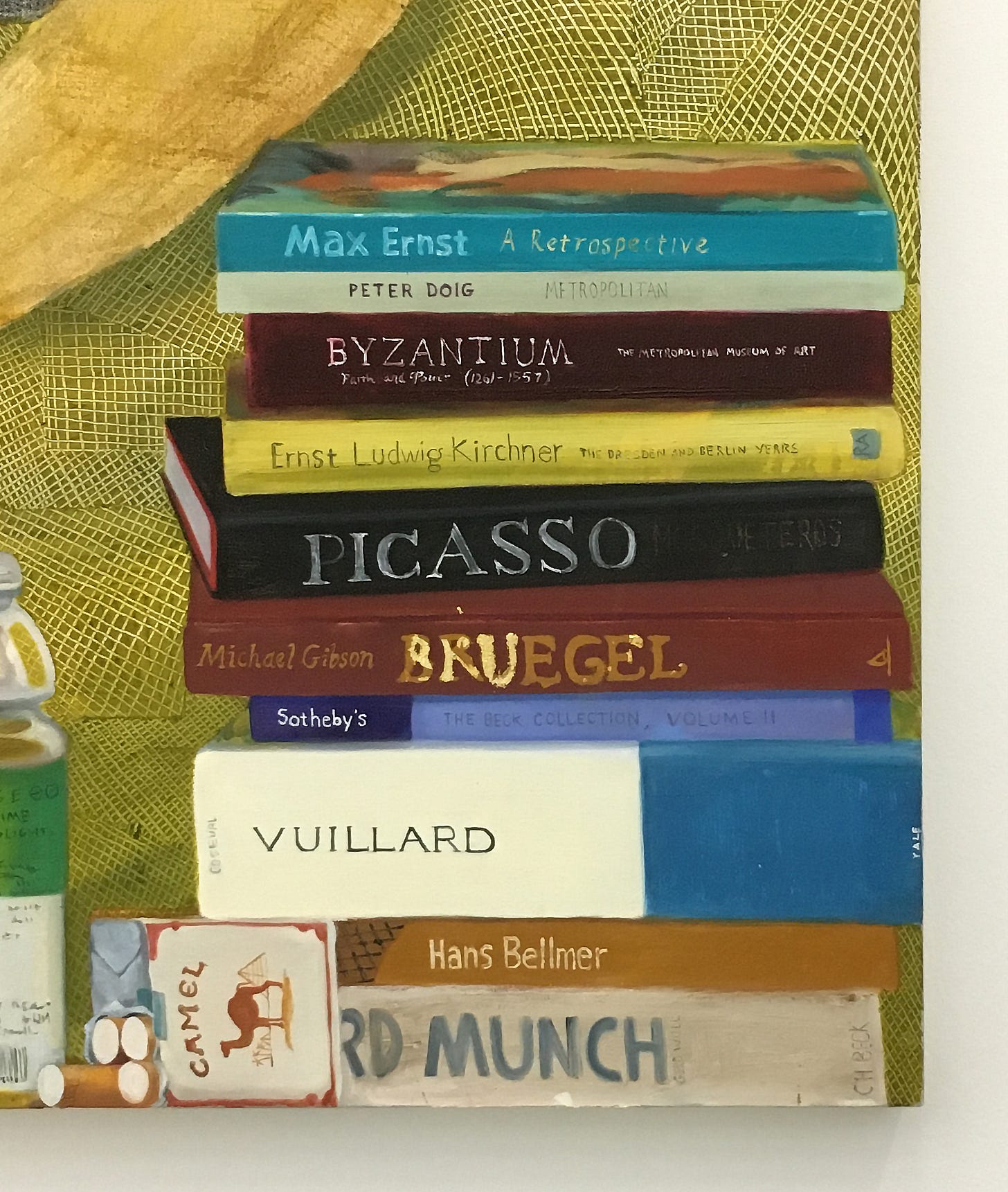

Like the drink bottles and cigarettes packet, these books are so legibly painted as to be identifiable. Many of them, as well as those in a second pile behind the mattress at foot level, fall into the genre of catalogue accompanying exhibition. Big and colourful souvenirs, with exteriors made to show off and shout out the artful delights within, these are books that serve as both the intellectual and often most expensive commercial product of an exhibition. The distinctly painted spines of Night Studio reveal the name of the exhibition, usually that of the bigname artist, and sometimes also the publisher’s name or logo.

While the exhibitions that these catalogues accompanied took place between the 1980s and 2000s, making them believable items in Eisenman’s 2009 studio, they mainly deal with a range of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European artists, from Matisse and Nolde (in the pile at the back) to Kirchner and Vuillard (at front), together with a few other art-related titles, such as Michael Gibson’s 1989 book on Bruegel and, just below it, a Sotheby’s auction catalogue from 2002.

Most of the books surrounding the figures in Night Studio are large and heavy, and thus difficult to read while lying supine (I’ve often tried). Like the one cigarette sticking out from its packet, they seem arranged more for our benefit than for the use of the models in this studio covered in splotches of paint resembling a night sky overly full with stars – or, just as well, the galaxy desktop background projected onto the wall behind two intertwined figures in Eisenman’s later, bookless painting, Morning Studio (2016).

Recounting how Night Studio first came about, Eisenman has described friends coming over, having some drinks, and posing themselves: “I mean it was their spontaneous, like, lying on top of each other, and I had the canvas set up in front of them and painted them from life.” There is no mention of the books lying on top of each other in this large picture most recently on display at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, as part of the travelling exhibition Heads, Kisses, Battles: Nicole Eisenman and the Moderns (and reproduced, in turn, across the covers of its catalogue).

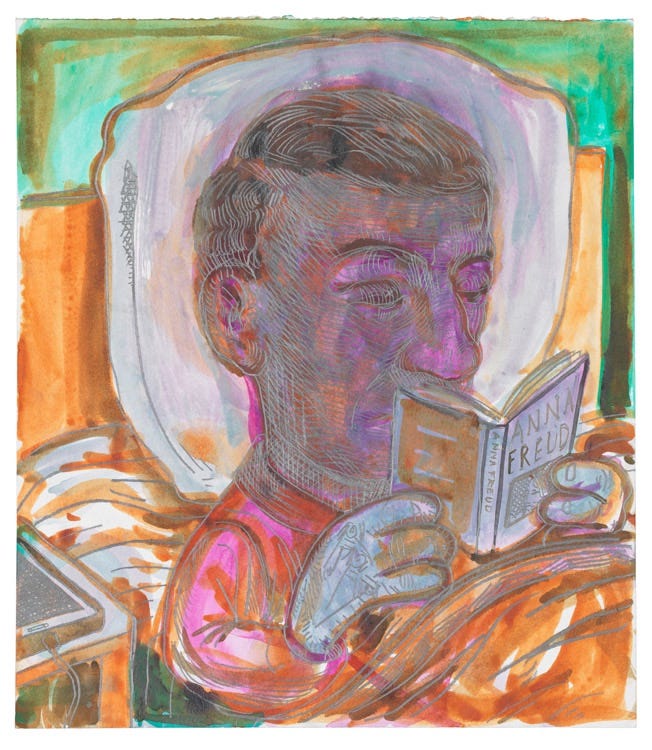

In this exhibition, Eisenman’s paintings and works on paper are shown together with those by a range of “moderns,” from the already mentioned Nolde and Kirchner to Alice Bailly and Charley Toorop. So Paula Modersohn-Becker’s Self-Portrait with Brush in Raised Hand (1902) accompanies self-portraits by Eisenman, including Self-Portrait at Night (2015), of the painter not with a brush in hand but instead tucked up in bed reading what is identifiably Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s biography of Anna Freud. The child of a psychoanalyst father, Eisenman reads a book about the child of the father of psychoanalysis. On the bedside table, a phone is charging. At least in this moment, the reading ego is beating out the scrolling id.

In the long history of painting, books turn up often. To represent them is not difficult. Simply make two rectangles share a spine, or, when the book is meant to be shut, a single rectangle will do. Text can be suggested with a few dashed-off illegible marks (as Liselotte Moser does in Lights and Reflections, which I look at in Art Jahr). But it also needn’t be at all; just the shape of the book is often symbol enough. Yet in the recent decades of still more prophesying about their impending death, books with readable titles are found in healthy number in contemporary paintings, and with surprising frequency they are books on art.

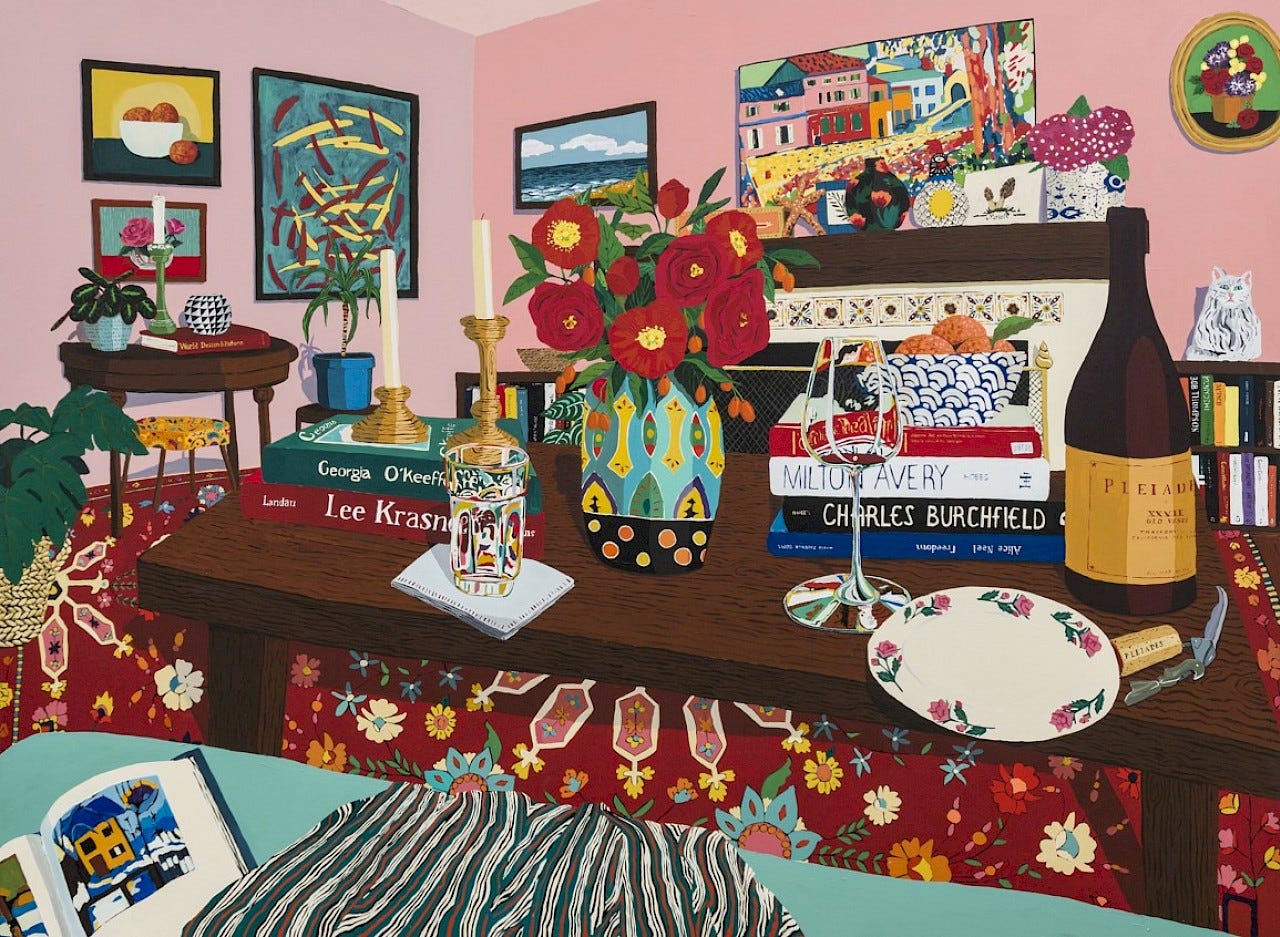

Take, for instance, the work of Hilary Pecis, in whose unpeopled interiors, filled with museum giftshop paraphernalia, viewers can enjoy some bookspotting. Many identifiable art books sit and rest closed in her paintings, while a few also lie open to works by, among others, Gabriele Münter, Georgia O’Keeffe and Matthew Wong. As Pecis’ meticulous rendering of these full-page colour reproductions makes clear, this sort of book is hardly meant for reading.

While Eisenman has made the books’ spines easy to read in Night Studio, it is the figures that are more obscure. Their bodies, in washes of pink and yellow, have been scratched and scuffed, making it look as if they are separate from, and older than, the painting that surrounds them. Eisenman seems to want us to think that this pair, with their old-timey hats, might in some way come from one of the books around them. The viewer is being goaded into art historical source-hunting by a painter who has been likened to, in the words of an exasperated Terry Castle, “virtually all the great artists in the Western figurative tradition.”

I won’t, then, mention Toulouse-Lautrec’s recumbent models in his studio paintings, especially when another painting lurks within Night Studio. Max Ernst’s Attirement of the Bride (1940) is reproduced on the cover topmost on the front stack.

Within Ernst’s painting is a framed decalcomania picture that repeats the feathery figure of the eponymous bride, a recursive detail lost in Eisenman’s reproduction.

Another catalogue in the front pile is for an exhibition of works by the less famous surrealist Hans Bellmer. The patch of grid on its spine is from Bellmer’s Cephalopod 1900 (1939/49).

This “cephalopod” is not an ink-squirting mollusc, but a jumble of human body parts, including limbs in striped tights, positioned on an undulating surface with a gridded, netlike pattern that carries on in the electric yellow mattress of Night Studio.

Both in Eisenman’s painting and in the exhibition recently based around it, the viewer is made to wonder about the connections between paintings, and between painters. With the books in Night Studio, Eisenman seems to be reflecting on the cephalopodic habits of the art world, and how paintings themselves get read.